Louise, Julie, “till you wish the lot were at Timbuctoo”, he said. I began to wonder if he were quite as serious as he looked.

Louise, Julie, “till you wish the lot were at Timbuctoo”, he said. I began to wonder if he were quite as serious as he looked.

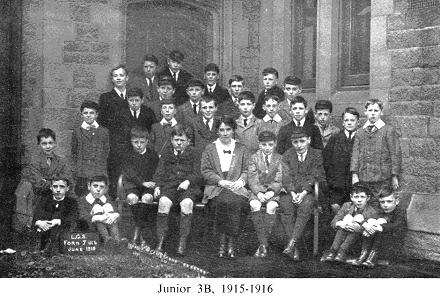

Mr. Stockdale, known as ‘Stocker’, I remember best as a splendid photographer. He made wonderful coloured plates, he was very good in offering to photograph one’s form. I still have the one he took of me and my first form, several of whom, alas, were killed in World War II.

Miss Wynne-Edwards, the Head’s sister, was form mistress of Junior I, and had been there since 1909. Like all the rest of the family she was utterly unselfish and marvellously kind.

Naturally I felt rather nervous when I started teaching. I never had much real difficulty with discipline, though I must own I was rather frightened of the first Junior I.

THE WORST lesson I remember was once when I had to take a fifth form for French, in someone’s absence. My cousin, at whose home I lived, was in that form, so were many of his friends whom I had met out of school and who knew me by my Christian name. They gave me rather a bad time, I can remember how I trembled all through the lesson. One or two boys stayed behind and argued with me about my translation of various words.

The small boys had been used to saying, “Please sir.” I rarely got “Please miss”, but very often “Please”. I asked one boy in my form if he had enjoyed his holidays and his reply was, “Yes thank you, Please”. I was sorry when the name was dropped; I liked it. Of course, I know that I have been called ‘Ma Christie’ from the day I arrived, as Miss Wynne-Edwards was ‘Ma Winnie’, and Miss Jones ‘Ma Jones’.

The small boys I have always found very friendly and forgiving. I have met one boy only who ever bore a grudge. If one had been snappy or bad tempered owing, perhaps, to a headache, after a rather stormy lesson, those who had been most in ‘hot water’ would come with a smile and offer me chocolates or toffee. I have had to accept (or refuse) some queer gifts:—a bite from an apple—the first bite!—a drink of cocoa from a flask, an orange, and even half a biscuit. In recent years, when sweets were rationed, a small Scot in my form solemnly presented me with a sweet or a chocolate biscuit at the beginning of each break. If I protested he would put it on my desk and dash out of the room.

AS A RULE I have found young boys most thoughtful and very generous. An aunt of mine was killed in a motor accident. My form must have noticed my distress. They subscribed and gave me a bunch of lovely flowers. One Christmas term I had a very unruly form who took a great deal of ‘taming’. Just before we broke up at Christmas, I held forth for about a quarter of an hour, telling them exactly what I thought about them. When I had finished, one of the worst offenders came and laid a parcel on my desk and said, “We all wish you a Merry Christmas”. The present was a very nice brown handbag. Naturally I was rather overcome and very grateful. I asked them how they had come to choose a bag, who chose it and where it had been bought. Reply: “Bridges—we got it cheaper there”. One of the Bridges was in the form.

One never appealed in vain for money. Whether it were Belgian Refugees, Red Cross, Chapel Window Fund, War Memorial, Doctor Barnardo’s or Wounded Soldiers, the response was always beyond my expectations. I must have been instrumental in raising quite £300 for various causes. A few years ago, I told my form that I was going to have a system of fines for untidy desks, a penny or a halfpenny, according to the state of the desk, and that we were going to give the money to the Ministry of Pensions Hospital. Immediately there was a cry of “May we give something to that now?” Before I knew quite what was happening there were three or four shillings on my desk! That upset my system of fines somewhat.

As I look back I remember great kindness, politeness and consideration from nearly all boys I have known. In the old days if one were carrying a case or parcel, one heard running feet and an offer to carry whatever it was. I remember this happening in Clarendon Road, as I was carrying a suitcase to Sheafield, to stay with the Wynne-Edwards. Hardly had the boy taken it when there were other heavier footsteps—the Head—he took the case from the boy, and then reprimanded me mildly, telling me never to let a small boy carry a heavy case as it might injure him. From the Head, too, I learned something more about the treatment of small boys. He saw the secretary put her arm about a very small, forlorn-looking boy. I heard him say to her, “You put your hand on that boy’s shoulder. Never do that. Little boys like to think they are men, and it lowers their dignity”.

BOYS WERE always very willing to give up their chairs to grown-ups. At a Speech Day at the University Hall four boys near me jumped up and offered their chairs. I have a dirty piece of paper in front of me—it was put on my desk the next day:

“Miss Christie,

From a freind whose’s chair she did not axcept yesterday.

Yours deaply offended.”

There is no signature, but I well remember who it was. The same boy, by the way, was most gallant, and told me that my dress was the nicest in the Hall!

A vivid memory of those early days was the readiness of all boys to own up to anything they had done wrong. Hardly had one said, “Who did that?” than there was a hand up. The boys were mischievous enough, but were never cowardly and were quite ready to take any punishment.

_____